By Adam England, the Backyard Astronomer

The Greeks coined the term planetes – meaning “wanderer” – to describe the objects they saw in the sky that regularly moved against the background of the other, fixed stars. Over time, this included many bodies that wander across the night sky, including the moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, as well as smaller bodies like Sedna, Eris, Ceres, and Pluto. The strict definition of a planet has caused heated debates between individual astronomers, professional observatories, and universities, which have pockmarked history like the craters of our Moon. The International Astronomical Union, or IAU was founded in 1919 as a consortium of astronomers from all over the world, with the mission of cooperative astronomical “research, communication, education and development”. As such, the IAU has become the definitive organization for the uniform classification and naming of our continued discoveries across space.

Since the first telescopes appeared around 1608, we have been able to observe much more than the easily visible stars that have graced our skies and mythologies for thousands of years. Commonly known stars such as Polaris, Betelgeuse, Rigel, and Vega were soon joined by many hundreds of others, which were often assigned designations, usually relative to the name of the discoverer, and the chronology of which it was discovered. For example, German astronomer Wilhelm Gliese (pronounced GLEE-zə) published a 1957 catalogue of 915 stars that were within 20 light years of Earth, essentially our closest stellar neighbors. The majority of these continue to carry designations like Gliese 436, being the 436th star listed in the catalogue. Not nearly as fun to say as Betelgeuse, the IAU has developed periodic naming competitions for some of the more interesting and commonly studied of these many thousands of additional stars sans moniker. Astronomers, educators, students, and laypeople alike contribute to these competitions, with the winning epithets from around the world are now represented in the heavens.

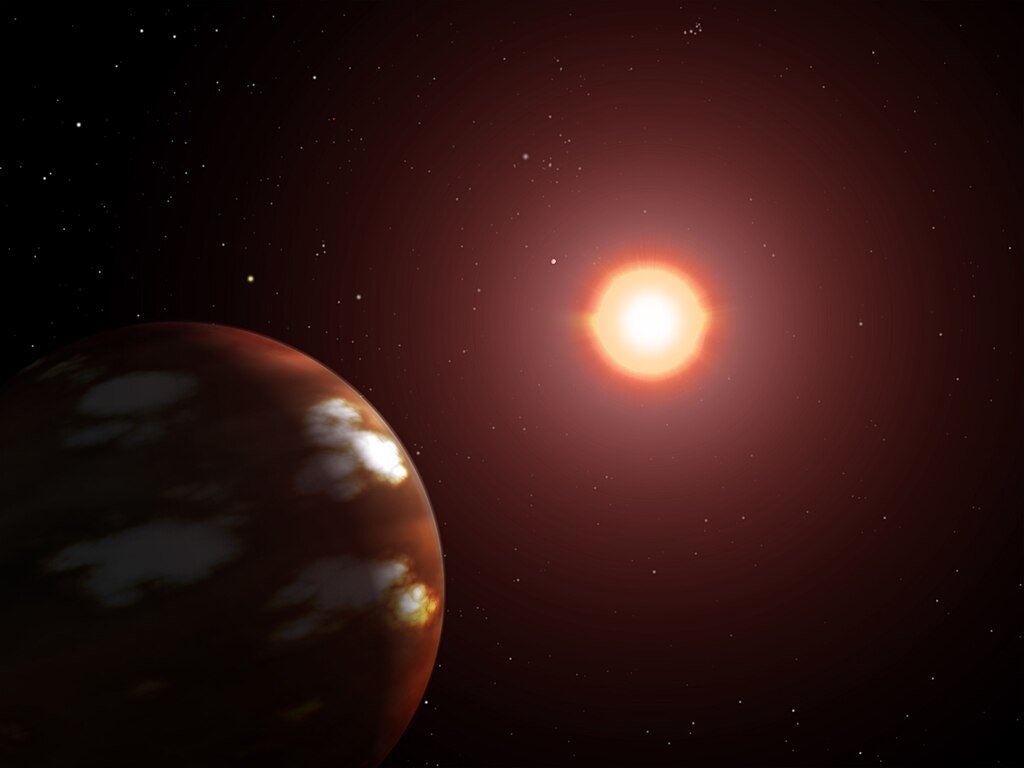

In 1992, the first exoplanet was confirmed. Exo being the Greek for “outside”, the IAU has defined an exoplanet similar to that of a planet, being a body which regularly orbits its host star, with a gravitational pull great enough to have cleared its orbit of other smaller bodies, and with the caveat of existing outside of our own solar system. Finding these exoplanets is difficult, and only a handful have been directly imaged. Most are discovered through various methods including how their gravity tugs on a star as it orbits and making the host star “wobble”, or by measuring the dip in light observed when the exoplanet passes in front of its star as measured from our view. Since that first discovery in 1992 by researchers at Puerto Rico’s now defunct Arecibo Observatory, we have added more than 5000 confirmed exoplanets to the list of rocky, liquid, or gas bodies orbiting other stars. Commonly, they follow the naming designation of the host star itself, such as the hot-Neptune icy body Gliese 436b orbiting its red dwarf star approximately 32 light years distant.

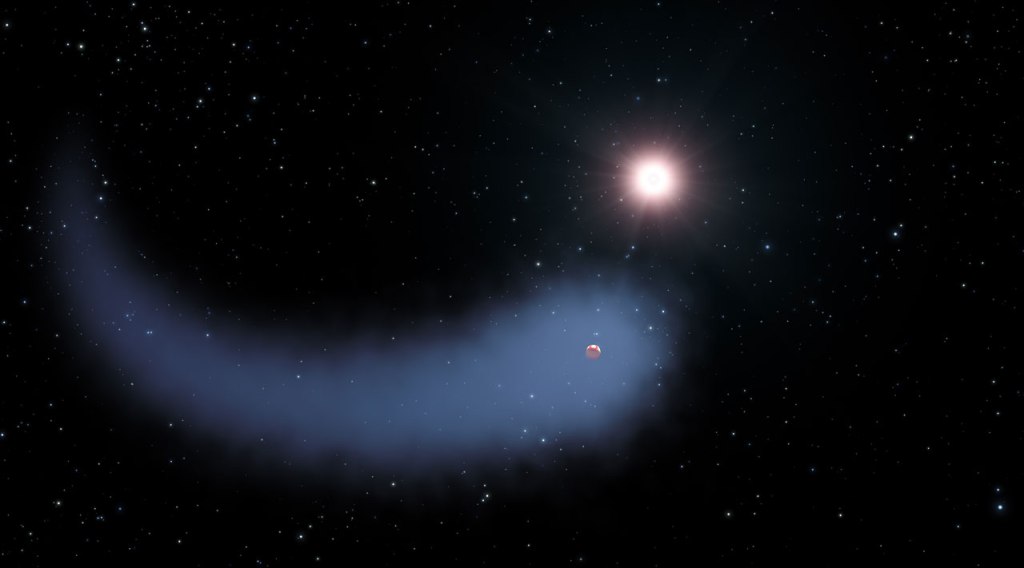

To learn more about these exoplanets astronomers have created ground-based observatories such as the Very Large Telescope in Chile’s Atacama desert, and space-based equipment like the James Webb Space Telescope orbiting with the Earth at 4 times the distance of the moon. The sensitivity of these telescopes, and ability to observe outside the visible light spectrum of optical telescopes, has provided information that allows us to measure the volume, mass, and atmospheric compositions of some of these exoplanets. For example, Gliese 436b was chosen as one of the first exoplanets to be studied by the JWST, after the smaller Spitzer Space Telescope previously suggested a composition like that of a giant ice world, albeit with extremely high pressures and temperatures in excess of 800F. The heat, pressure, and proximity to the radiation of its star at just 2.6 million miles suggested that a giant cloud of gas observed around the exoplanet was actually a comet-like tail stretching 9 million miles.

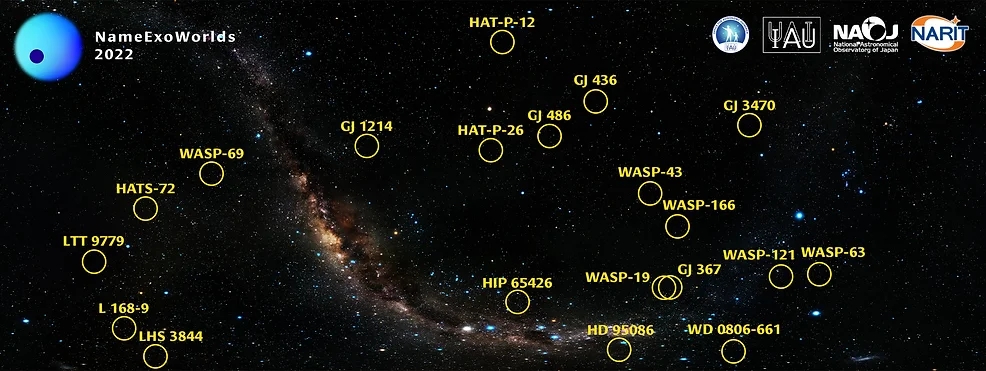

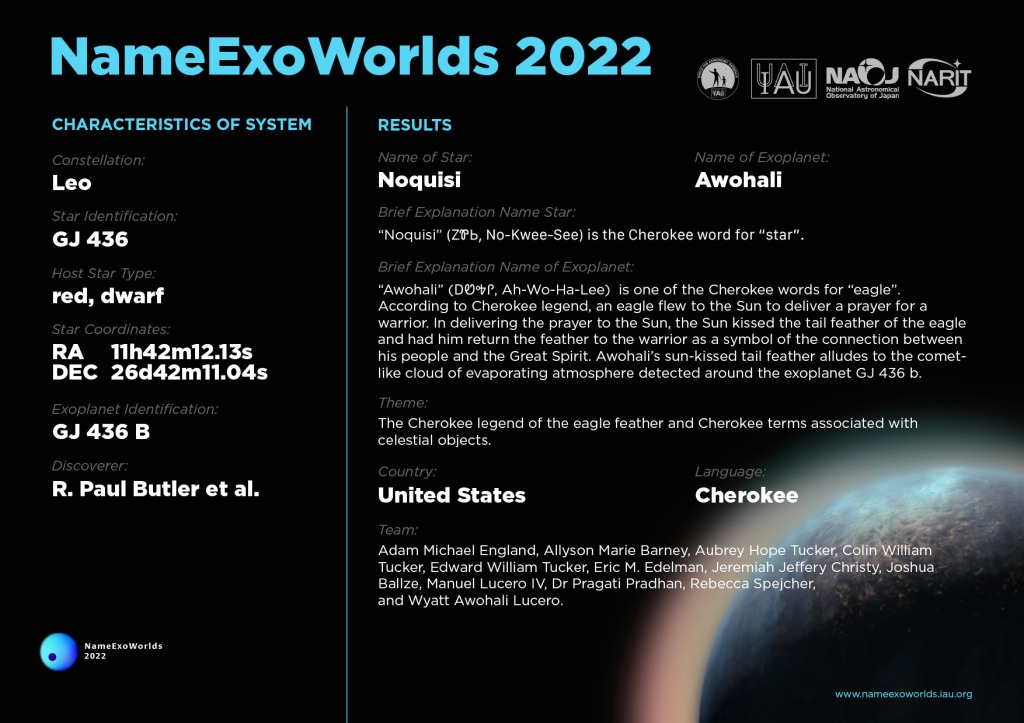

An exotic exoplanet, 21 times the mass of Earth, soaring around its star every 62 hours, with a surface of solid ice that exists at temperatures hotter than a household oven – and carrying the monotonous designation Gliese 436b. Something had to be done, and to this end, the IAU introduced NameExoWorld2022, an international competition to propose names for the more fascinating exoplanets that the James Webb Space Telescope will be dedicating time to observing. The theme for the NameExoWorlds2022 competition was “indigenous languages”, and so I assembled a team including representatives from Prescott’s Museum of Indigenous People, Embry Riddle Aeronautical University, The Northern Arizona Astronomical Consortium, and students from ERAU, Bradshaw Mountain High School, Northpoint Expeditionary Academy, and Liberty Traditional School. Together, we came up with submission for Gliese 436b and its host star Gliese 436, and have spent the last 8 months promoting this through in-person outreach events around the Quad City area, articles, videos, and podcasts available online.

On Wednesday, June 7th, the IAU announced that Gliese 436/b will now formally carry the approved names Noquisi and Awohali for the star and exoplanet, coming from the Cherokee language meaning “Star” and “Eagle” respectively. These names represent so much more than just two words picked at random from an indigenous language. They represent an oral history handed down for hundreds of generations telling of a connection between humanity, nature, and the stars, as well as the first time that a star or exoplanet have officially carried a name in the indigenous language of a North American people. As told by Manuel Lucero IV, Director of Prescott’s Museum of Indigenous People, and a member of the Cherokee Nation, the oral history of Awohali goes:

Long ago when animals chose to speak with us, there was a warrior who had a prayer for his people that he wanted to deliver to the Great Spirit. This warrior climbed a mountain as high as he could go, and he came across Yona, the Bear. Yona said, “Two-legged, what are you doing here? You don’t belong here!” The warrior said, “I want to deliver this prayer to the Great Spirit.” Yona was very taken aback by this story and says, “I will take that prayer for you.” He took the prayer and climbed as high up the mountain as he could. When he reached the top of the mountain and there were no more trees except for one, he saw Awohali the Eagle nested up at the top of it. Awohali looked down and said, “Yona, what are you doing here? You don’t belong here.” Yona told Awohali about the prayer, and equally touched, offers take the prayer. Awohali in Cherokee means “He who flies the highest,” and Awohali flew as high as he could, higher than he ever had before, all the way to the Sun – our star Noquisi. The Sun looked at the eagle and said, “Awohali, what are you doing here? You don’t belong here.” Awohali told the Sun about the prayer, who replied, “I speak with the Great Spirit all the time, give me the prayer and I will deliver it. But first, give me one of your tail feathers.” Awohali reached back and plucked one, handing it to the Sun, who kissed it. This is why the golden eagle tail feather has a black mark on the tip. The Sun told Awohali, “Give this feather to the people so they will know they have a direct connection to the Great Spirit.” For this reason, the eagle feather is coveted by most native people.

We are honored to share this story with you, as a small piece of the valued history of one of our country’s many diverse cultures, and as the members of the Prescott Area team who worked so diligently to share it with the world, for now and for generations to come. I urge you to take an afternoon and visit the Museum of Indigenous People at 147 N. Arizona Avenue to learn more about the Noquisi/Awohali system, the NameExoWorlds2022 competition, and indigenous astronomy at the Ani Noquisi exhibit running now through December 2023, and follow the Jim and Linda Lee Planetarium at Embry-Riddle for more upcoming shows on this and other astronomical wonders. Additionally, a video of the project is available at https://youtu.be/nl893hO6v5w

Members of Team Ani Noquisi:

-Manuel Lucero – Director, Museum of Indigenous People; Representative of the Cherokee Nation

-Joshua Ballze – Trustee, Museum of Indigenous People; Jurassic Paleoart Expo; Representative of the Hia-Ced O’odham Nation

-Dr. Pragati Pradhan – Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy, Embry Riddle Aeronautical University; Association for Women in Science

-Eric Edelman – Director, Jim and Linda Lee Planetarium, Embry Riddle Aeronautical University; AAS Astronomy Ambassador, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee of the International Planetarium Society

-Edward Tucker – Realtor, Licensed Drone Pilot; Videographer

-Adam M. England, E.A, “The Backyard Astronomer” – Founding secretary, Northern Arizona Astronomical Consortium; Former Vice-President, Prescott Astronomy Club; Astronomical League member

-Rebecca Spejcher – Undergraduate Student of Astronomy, ERAU; Society of Physics Students

-Colin Tucker -Student, Bradshaw Mountain High School

-Wyatt Lucero – Student, Northpoint Expeditionary Learning Academy

-Allyson Barney – Student, Liberty Traditional School

-Jeremiah Christy – Student, Liberty Traditional School

-Aubrey Tucker – Elementary School Student