Imagine watching the formation of our Solar System some 4.5 billion years ago. From an omniscient view, dozens—perhaps hundreds—of planetoids are jockeying for position, carving out orbits around a newborn Sun. Smaller asteroids and comets ricochet through the chaos, colliding by the millions and leaving behind scars that will last for eons.

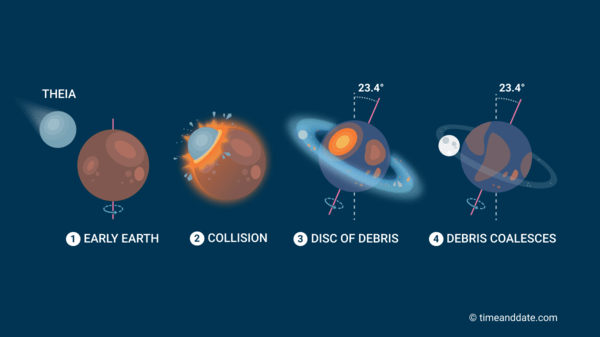

The most spectacular moments come when two of these young worlds meet on a collision course. In one such cataclysm, the infant Earth—only slightly larger than its neighbor Theia, a planet about the size of Mars—was struck in a glancing, world-shaping blow. The impact nearly destroyed the young Earth, melting much of its surface and leaving its core molten to this day. The debris flung into orbit eventually coalesced into a single, stabilizing companion: our Moon.

That new satellite formed surprisingly close—only about 240,000 miles away. For perspective, Neptune’s distant moon Neso orbits more than 31 million miles from its planet. By cosmic coincidence, the Sun is about 400 times farther away than the Moon but also about 400 times larger, a pairing that grants Earth one of the Universe’s rarest sights: a perfect total solar eclipse. Few, if any, other worlds enjoy such precise alignment.

Because the Moon formed so near, it soon became tidally locked to Earth. Over time, Earth’s gravity slowed the Moon’s rotation until it matched its orbital period—one turn every 28 days. As a result, we always see the same face of the Moon, while the far side remains hidden from our view.

Of course, the so-called “dark side of the moon” isn’t truly dark (sorry, Roger). Just like Earth, one half of the Moon is always lit by the Sun. Its familiar waxing and waning are simply the geometry of sunlight and shadow as the Moon orbits Earth. Each lunar “day” lasts 14 Earth days, followed by 14 of darkness—a rhythm that has ruled our tides, nocturnal skies, and even the biological cycles of life for billions of years.

For astronomers, though, the best lunar phase is the new moon, when our satellite’s glare fades and the heavens open wide.

This month offers both extremes. The Full Beaver Moon on November 5th will be the largest and brightest supermoon of the year. Just two weeks later, the new moon on November 20th will bring prime observing conditions for the autumn sky. The Leonid meteor shower will peak that week, and Uranus—at opposition on November 21st—will shine at its brightest, visible as a faint blue dot near the Pleiades through a good pair of binoculars.

So step outside, look up, and remember: every phase of the Moon is a reminder of the cosmic collision that made life on Earth—and our night sky—possible.

Observer’s Quick Notes

- Full Beaver Moon: Nov 5 – year’s brightest supermoon

- New Moon: Nov 20 – darkest skies for deep-sky viewing

- Leonid Meteor Shower: Peaks Nov 17–18 (20–25 meteors/hour)

- Uranus at Opposition: Nov 21 – near the Pleiades; binocular visible as faint blue dot

BackyardAstronomer #AmateurAstronomy #Supermoon #Leonids #UranusOpposition #NightSky #STEM #ArizonaAstronomy