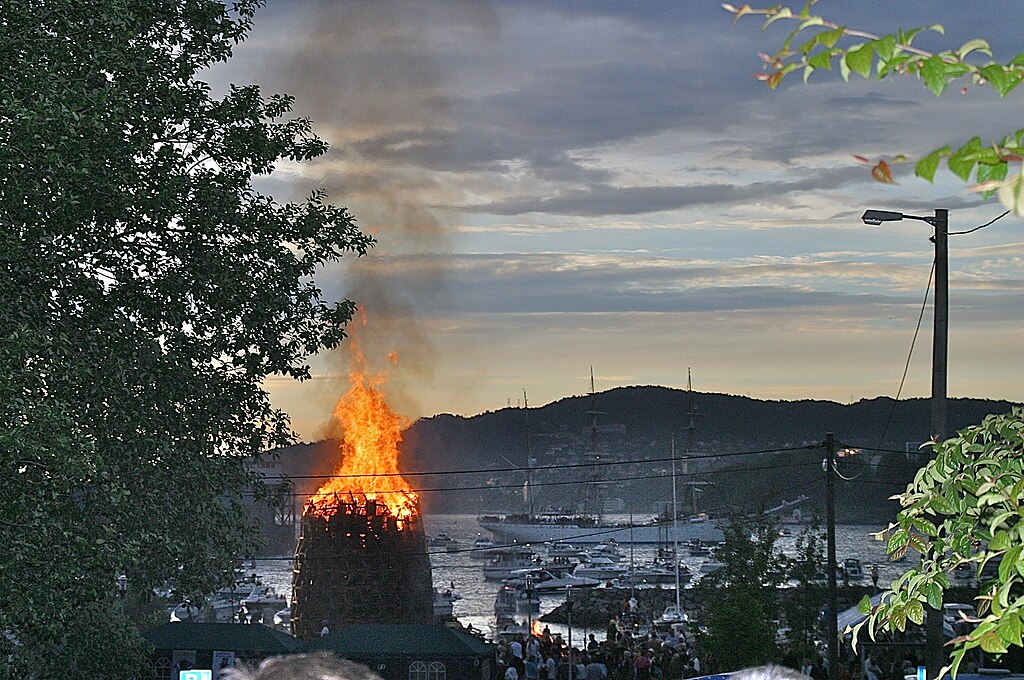

The celebration of solstices and equinoxes are documented in almost every culture worldwide. Varying types of events have become regional staples, especially in the Northern Hemisphere, where the date around June 20-21st each year represents the longest days and most sunlight, before the Sun begins its semi-annual trek back to the South. In Sweden, one may encounter a Midsummer celebration with revelers dancing around the maypole, adorned in festive attire, while neighboring Norway celebrates with massive bonfires. As Christianity spread across Europe, many of these ancient rituals merged with the traditional birthday of Saint John the Baptist on June 24th, for deeply religious symbolism. In Barcelona, communities commemorate the holy day with feasts and bonfires fires lit from the Canigó Flame, burning continuously since 1955. Comparatively, Alaskans celebrate the long summer sun in many ways, including a midnight baseball game in Fairbanks – with no artificial lighting – and indigenous games and a “polar bear swim” in Nome.

Possibly the most well-known solstice events occur at ancient megaliths. The 5,000 year old Ħaġar Qim site in Malta was built so that the solstice aligned a hole in the wall to create a crescent shaped light that morphs into an ellipse and the disappears as if sinking into the ground. The most famous of these is Stonehenge, where thousands will gather this year to witness the Sun rise behind the Heel Stone.

It could lead one to believe in ancient alien conspiracy theories, that so many cultures, separated by thousands of miles and thousands of years, all did a pretty good job of coordinating with the modern calendar. Archaeoastronomers, however, know better. From the solar alignment of the Temple of Kukulcan at Chichen Itza, to the layout of the entire Angkor Wat complex in Cambodia, humans have observed the sun, measured its movements, and calculated its future positions for thousands of years.

Venturing across the Central Highlands of Northern Arizona, one can also find such monuments left in the strata of history. The indigenous inhabitants of these lands as well as passing travelers left their marks on the landscape, as evidenced by ruins and petroglyphs found throughout the area. One such location is Solstice Mesa, nestled in a protected park in Prescott Lakes at the end of Tawny Drive. Rock art throughout this short hike tells the story of thousands of years of regional inhabitation, as well as the record of the changing of the seasons. This monolithic ephemeris aligns with a crag in Granite Mountain at the Summer Solstice, and again with Thumb Butte at the Winter Solstice. Such an alignment cannot be mere coincidence, and silently speaks to the advanced astronomical understanding of the early Yavapai and other peoples who have called this land home.

Should you visit, please use the opportunity for discovery and enlightenment to respect this sacred place. To learn even more about the indigenous cultures of Northern Arizona, visit the Museum of Indigenous People at 147 N Arizona Ave in Prescott.