By Adam England, The Backyard Astronomer

Stuck on Earth, we essentially get one viewpoint of the cosmos. From a nearly fixed location in the universe, it doesn’t seem like other objects move very much, apart from the “wanderers”, as coined by the Greeks with the term “planētēs,” or planets. Due to the tilt of the Earth’s axis at 23.5 degrees, and as our planet orbits the Sun, we do have the opportunity to view different parts of the night sky at different times of the year. This gives us various constellations, that while they no longer match up to the ancient months of astrological charts, do progress through our skies over the course of one orbit, or year. But, as we know, Earth is not the only orbiting body running laps around the Sun. And, as it turns out, Earth isn’t the only planet that leans to the side either.

The early Solar System was complete chaos. Over nearly 500 million years, a giant cloud of gas and dust coalesced around the Sun, and gravity pulled debris together into gassy and rocky clumps – both large and small. Run-ins between these bodies were common, and one such collision knocked the early Earth sideways, giving us the 23.5 degree tilt, and therefore seasons. While we can’t rewind and watch a replay of these planetary fouls, the tell-tale signs of such impacts are scattered across the Solar System.

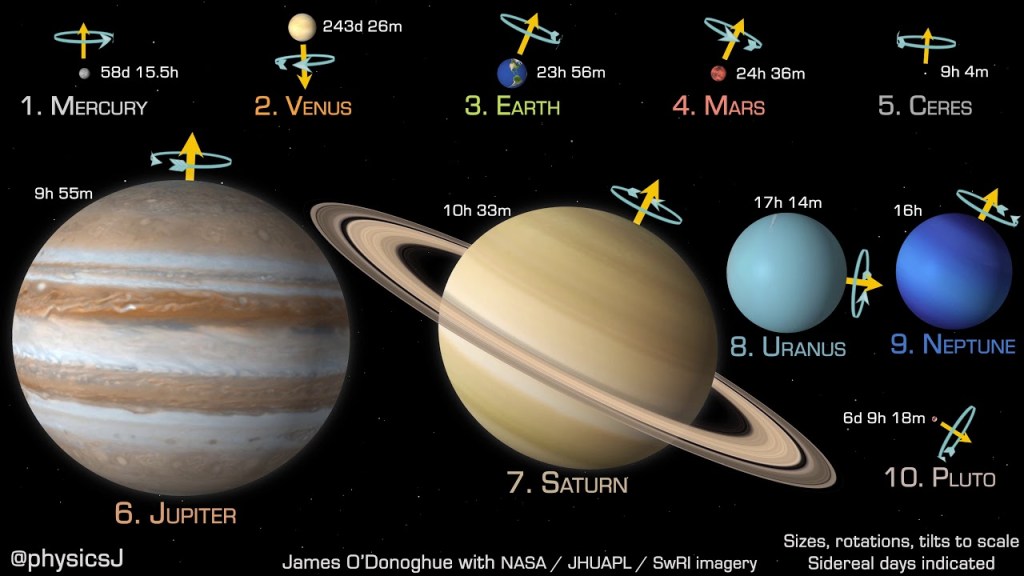

Ironically, Mars isn’t much different than Earth, with a tilt of 23.98 degrees. Jupiter can clearly take a punch, because it barely leans at 3 degrees. Saturn sits at 26.73 degrees off kilter, and Uranus is completely sideways, rolling down its orbital plane at 98 degrees. Venus took a knockout blow at some point, as it spins on its axis at 177 degrees, or almost completely upside down, and backwards of everything else in our stellar neighborhood. The larger planets must have protected their little brother from these celestial scuffles, as Mercury is the only known body in our Solar System with no tilt at all.

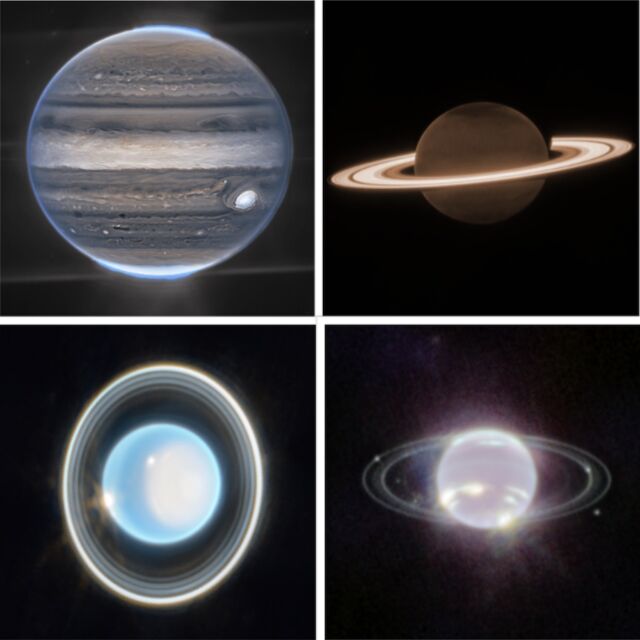

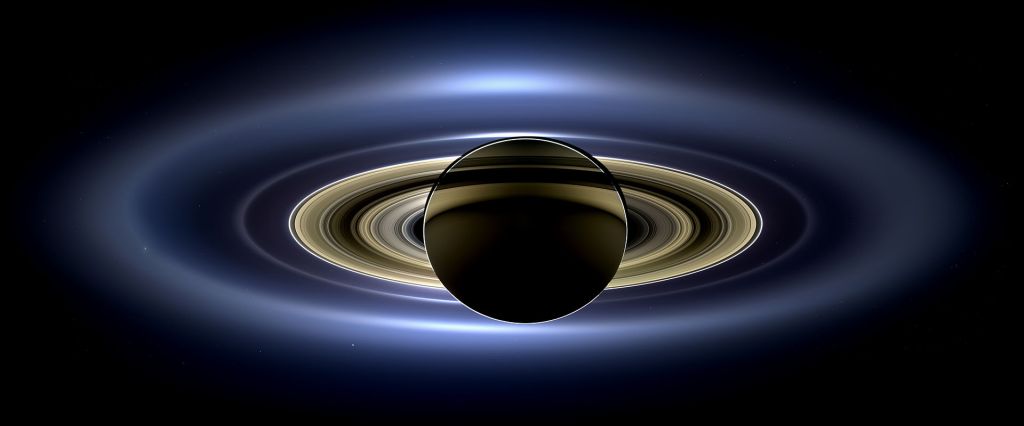

These cosmic accidents left debris fields in their wake, proof of which are the rings that grace the four gas giants of the Outer Solar System. Galileo was extremely perplexed by this unique shape he gazed at through his early telescope, and while he likely never fully understood the oblong shape he saw, those who followed have certainly been entranced by Saturn’s rings. Like countless astronomers before, seeing the rings of Saturn through a backyard telescope is what truly solidified this author’s passion for space.

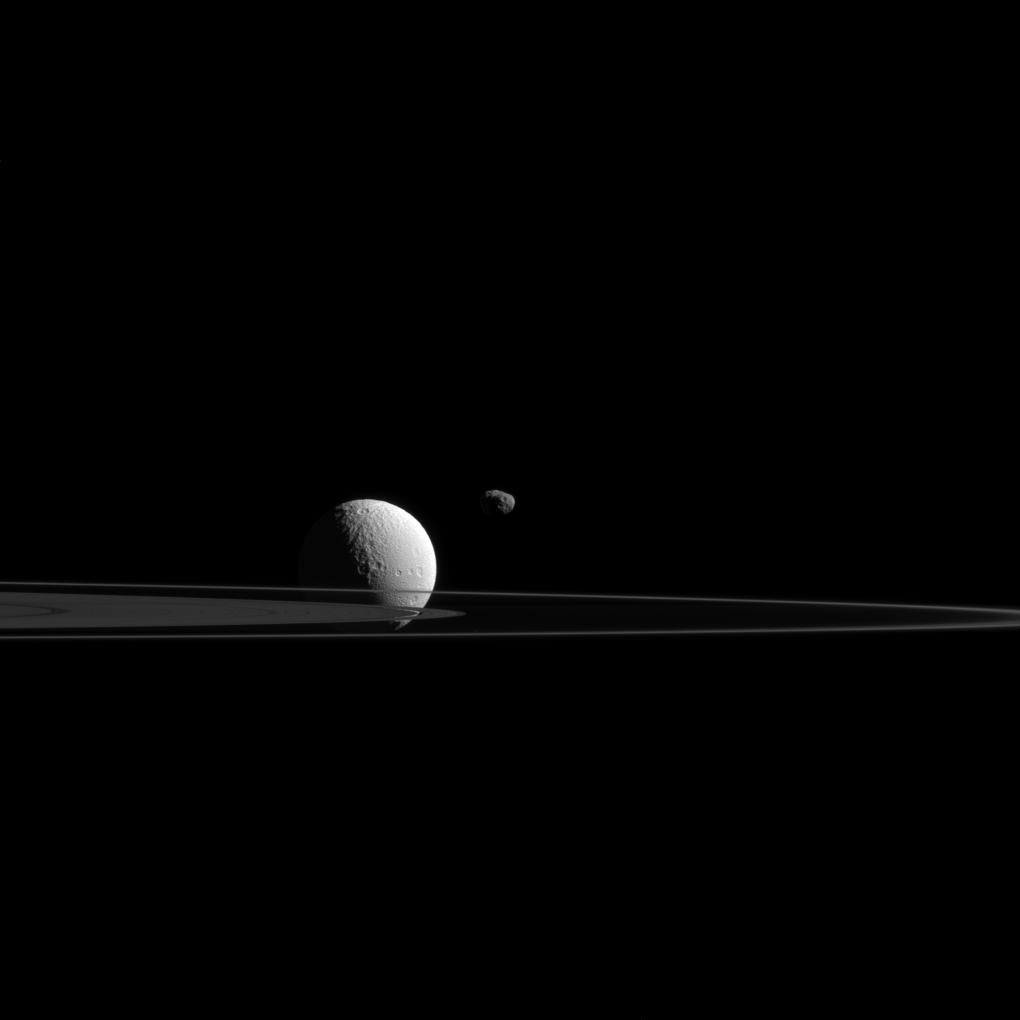

Over 400 years of study have documented the changes in Saturn’s rings, from both far away and up close, and across the entire spectrum of visible and non-visible light. The Cassini probe orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017, and gave us an understanding of the rings’ structure as billions of small pieces of snowy dust, ranging in size from a grain of sand to a small house. The overall depth of the rings averages less than 1 kilometer in thickness. Amazingly, at nearly 1 billion miles distant, we can still see these rings from our vantage point on Earth.

Sometimes.

Because Saturn is tilted at its respective 26.73 degrees, the rings can be viewed at different angles depending on how they and Earth’s orbits align. About every 14 years, we see the rings as completely edge-on, and they essentially disappear. During the month of March, the rings will be at this edge-on angle relative to Earth, and seem invisible except to the largest of telescopes. Sadly, Saturn is extremely close to the Sun this month, and not visible to most amateur astronomers. However, as Saturn emerges from behind the Sun in the early spring mornings later this year, the rings will again begin to tilt toward our view, and offer backyard astronomers the world over one of the greatest sights in the heavens.

Adam England is the owner of a local financial services firm and moonlights as an amateur astronomer, writer, and interplanetary conquest consultant. Follow him on Instagram @TheBackyardAstronomerAZ and at http://www.ManzanitaInsuranceAndAccounting.com