Nearly 3,000 years ago, The Chinese Yi Jing or “Book of Changes” documented small, irregular concealments in the surface of the Sun. By 300 BC, both Eastern and Western cultures were documenting their changing views of our star, and the patterns that would grow and then disappear on its disk. English Monk John of Worcester is the first known to have captured these obscurations in his drawings dating to 1128, and just a year after Galileo showcased his first optical telescope in 1609, English astronomer Thomas Harriot turned one of these new inventions to the leading lady of our Solar System. Taking from the work of so may great minds before him, Danish astronomer Christian Horrebow first proposed a regular cycle in 1775, noting, “it appears that after the course of a certain number of years, the appearance of the Sun repeats itself with respect of the number and size of the spots.” By 1852, Swiss astronomer Rudolf Wolf compiled all the data available to him, finding an approximate 11-year period from one minimum through maximum and back to minimum. Choosing to begin with the best possible documented records, Wolf denoted February 1755 as the beginning of Solar Cycle 1, with Solar Cycle 25 having begun in December 2019, and estimated to peak during Mid 2024.

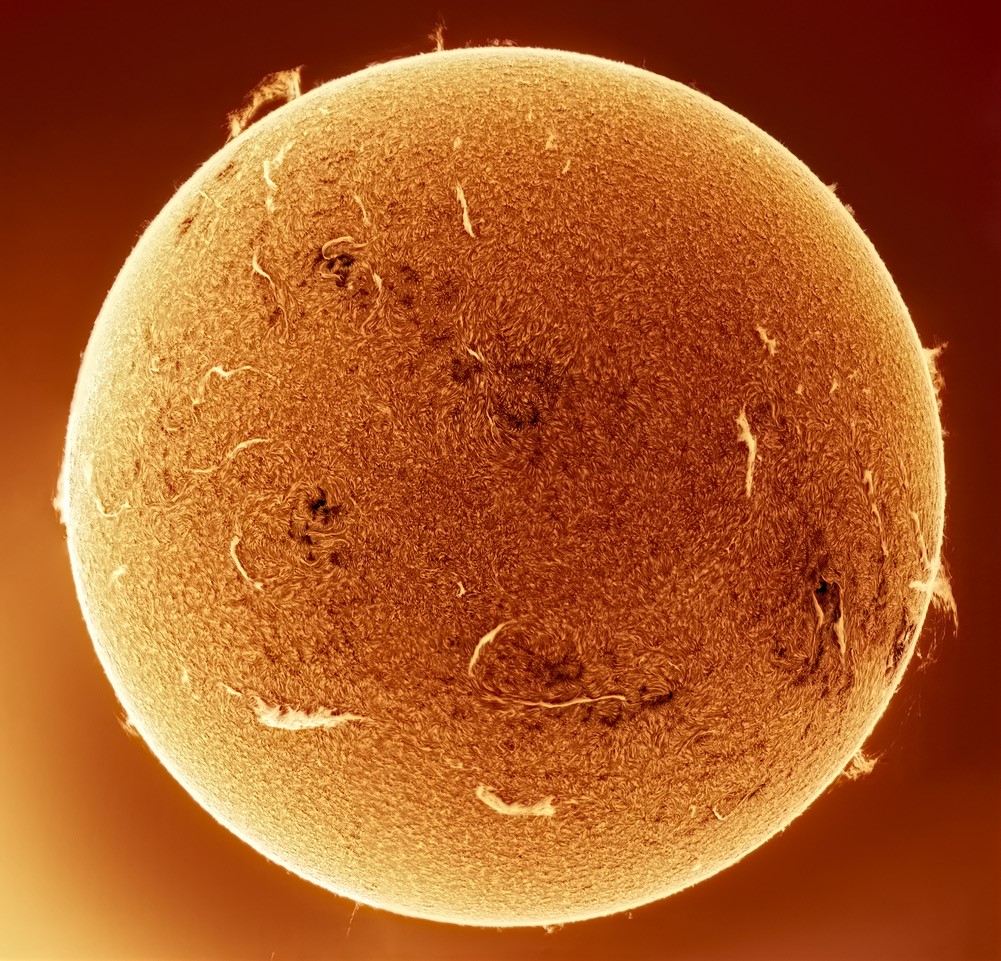

Though I must suppose these early solar astronomers spent much of their later years suffering from poor vision after a lifetime of staring at the Sun, we now have technology allowing anyone to document their own backyard observations of our closest star. The more complex Hydrogen Alpha (H-Alpha) filters allow an extremely narrow bandwidth of the light spectrum through a lens to the eyepiece of one’s telescope or camera sensor. The simpler form many of us are familiar with are the cardboard solar glasses you might find at an eclipse or other educational event, with lenses made of thin polymers reducing the sun’s penetrating radiation to the equivalent of shade 14 welding glass. NASA and the ESA have also provided us with the ability to view the sun remotely in many different wavelengths, courtesy of the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory – or SOHO – launched in 1995. Continuing to provide valuable observations of the sun nearly 30 years later, the SOHO Viewer app is available on most mobile platforms, allowing backyard astronomers to observe sunspots, prominences, and solar flares in real time.

More than just observing dark spots on the Sun, Solar Maximum can have diverse impacts on the environments of the Solar System. Periods of Solar Maximum may be accompanied by flares and storms, the largest of which are known as CMEs or Coronal Mass Ejections. In December 2021, Mars suffered a direct hit from a CME, and both orbiting and ground craft there documented how it affected the Martian atmosphere. Closer to home, 1859’s Carrington Event during Solar Cycle 10 caused Aurorae to be visible from the poles to the equator. Telegraph operators worldwide experienced electrical shocks, disconnected the power from the equipment, and were still able to send and receive messages, with some operators reporting better transmission for up to two hours, despite not being connected to a power source. Multiple telegraph offices even reported fires starting from such high electromagnetic activity.

Check with your local library and the Prescott Astronomy Club for events relating to the April 8th solar eclipse, and use your safe viewing instruments to enjoy this event and document the number of sunspots and prominences you observe during this Solar Maximum.